A Sip

Happy St Valentine’s Day blogworms! I pray you are well in the love of our Lord. I’ve actually just got back from a camp this weekend with our Christian university group (BCC) which was fantastic, but nonetheless tiring as usual. Being held this weekend, the theme for Camp was ironically on “Love”. And seeing as I’m still ‘feeling the love’, I thought what would be more appropriate than writing a blog on this very topic – love. But far from writing the usual commercialised secular sentimental dribble that is typically churned out during this day, I thought I would write not on our mushy-gushy love, but on God’s real and genuine love.

Whilst this may seem like a pretty simple and well understood topic, I hope to reveal to you how much we fail to begin to comprehend how complex the love of God really is. Rather than being a simple truth grasped by everyone, it is a truth which is not only taken for granted, but is so frequently incorrectly applied. Instead of going off what we think God’s love means based on our own prejudices and agendas, what God Himself says about His love through His Word needs to be regularly studied and meditated deeply upon. In fact, I can think of no truth in Western contemporary society that is more widely believed, talked about and affirmed, yet is so fundamentally perverted, distorted and misunderstood, than God’s love.

To help me do this all, I will draw heavily from a little book I just read by D.A. Carson called “The Difficult Doctrine of the Love of God”. As always, for anyone who feels this blog has not fully satisfied their questions, I would highly recommend reading this book (and the Bible of course!). Though small and palatable, it has been a great aid in my understanding of this topic, revealing many an unexpected insight into this intriguing and mysterious subject matter.

Spring Time!

But before we plunge straight into this rich topic, lest you think I am exaggerating slightly by my dire assessment above, I will first show you an example of what I mean when I assert that the love of God is so widely distorted and misrepresented. The other night, I watched a Christian movie that I had been wanting to watch for some time. It is only a recent movie, but from what I had read and heard, the pretense of the plot had me hooked and interested. The movie is called “Joshua” and is based on a novel of what I can only assume is of the same name. The film is basically set up on the hypothetical question, what would Jesus do and say if He inconspicuously returned to a small rural town today? Sounds like a very interesting scenario, doesn’t it? It also sounds very dangerous. Whilst I was intrigued by the plot, I was also concerned about its possible profane portrayal of Jesus as other extra-biblical representations of God and Jesus have shown such as the ever popular and heretical novel, “The Shack”. Nonetheless, putting my concerns aside, I watched the movie. Was I right? Did “Joshua” fall into the same category as “The Shack”? Was it heretical?

Well, to answer these questions bluntly, my concerns were not in vain. Whilst “Joshua” had some very relevant observations to make about the church and also had some very touching scenes which I must admit nearly spurred me on to tears, it also contained some very heretical representations and comments. Sadly, I think these unorthodox views are commonly held in Evangelical and secular circles. The Jesus character (‘Joshua’) is often not the same Jesus of the Bible.

Whereas the Jesus of the Bible would have had quite a bit to say on the heresy of the Roman Catholic church (which figures quite prominently in the movie), Joshua seems either indifferent or ignorant of any of these problems (Joshua even goes so far as to make a statue of the Apostle Peter, aiding the local Catholic church’s idolatry). In fact, whereas the Jesus of the Bible would have preached to the sinful inhabitants of the town about the Gospel, Joshua stays silent on this crucial message, seeming more interested in helping and empowering them. Whereas the Jesus of the Bible is the glorious Lamb of God; the Servant King who is to be worshipped forever by the Church; Joshua is portrayed as more of our buddy and life coach than our Holy King who seems more concerned about making our dreams come true (there is even one scene where Joshua grants a Catholic priest’s dream to become a cardinal without any mention of what God’s will is for the priest or Joshua correcting his heretical views).

All of these contrasts simply sum up the difference between the Biblical narrative of Jesus and the movie’s narrative. In the Bible, Jesus is the star and we are the supporting cast, whilst in the movie, the roles are reversed and we become the main cast and Jesus becomes our supporting cast. Was I surprised by this? Unfortunately, not really. I have come to expect this sort of narcissistic view being conveyed by now after reading such Christian commentators as Michael Horton who reveals how backwards we have Christianity in the West.

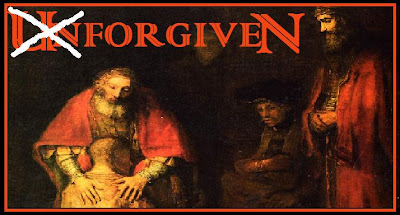

But perhaps the best example of these views (and the one which most relates to this blog topic) is displayed in a scene where Joshua goes to the local Roman Catholic church. After listening to the priest preach about sin, the fear of God and Judgment Day, Joshua is later confronted by this priest after the service who asks what Joshua thought about his sermon. Joshua replies with his typical non-confrontational indifference. This I can tolerate. What I cannot tolerate is what he said afterwards about the Bible. Whereas the Jesus of the Bible reveres and holds the Holy Scriptures in the utmost esteem; this same Jesus who replied systematically, “It is written…”, “It is written…”, “It is written….” to Satan’s temptations (Mt 4:4-10); Joshua shrugs off the Bible as simply a love letter between God and us.

Really? A love letter? Whilst people who have only a passing familiarity with the lovey-dovey parts of the New Testament may be able to buy into that, try telling that to the young congregant who is reading the wars of the Old Testament. Or the seemingly severe Mosaic laws. Or even eternal punishment in Hell. And when the priest’s fellow priests (and, though I never thought I would stand alongside Catholic priests on issues of sin and salvation, me also) pertinently ask Joshua about what the Bible says about sin, judgment and the law, Joshua again disregards all these with the simple reply of love. Love, it would appear, is all we need. In fact, it would appear that love is all God is. Without any mention of the Holiness, Righteousness and justice of God that the Biblical Jesus regularly and confrontationally preached about, Joshua not only paints a two dimensional picture of the Bible, but of God’s love and, dare I say, God Himself.

This is the issue at hand. So common is this view that it is very hard to divorce it from the Christianity we know and are presented with everyday. This view conveys that the Bible is simple to understand and subsequently, God’s love is likewise simple. What’s the answer to all life’s problems? It’s easy – love God and love your neighbour. You hear this on contemporary Christian radio, you read this in popular Christian self-help books and you see this in current Christian films. Heck, you even hear it from other religions and even secular society. “God loves you!” “Love each other!” If it was that easy, then God really wouldn’t have needed to send His Son in the first place. This world sure wouldn’t be in the state it is in if love was easy. It is precisely because true love is impossible for humans that Christ died on the Cross and gave us His Spirit. We as humans naturally hate God as He is and cannot love each other in the way God desires. These two human inadequacies are at the heart of the problem of sin.

What these proponents of this view have done is take a beautiful truth from Scripture, namely “God is love” (1Jn 4:8), and have twisted it to mean “Love is god”. As long as it is done in the name of love, it is good. God is not the answer anymore, love is. I don’t mean to be critical for the sake of being critical, but things really haven’t improved since the era of the Hippies. Different people, different means, but same old message. Love and peace are the ultimate aims; goals that must be accomplished at any cost, even if that cost is the truth.

D.A. Carson explains that part of the reason why the love of God is so misunderstood is that, by and large, our contemporary Western culture is no longer grounded in Judeo-Christian ideologies as it has been in the past, but is now grounded in secularism, post-modernism and pluralism. Whereas great writers in the past such as C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien could get away with saying “God loves you” without the need to go to great lengths to explain what this means, these days this phrase no longer carries with it the meaning that Scripture ascribes to it. As Carson says:

“The love of God in our culture has been purged of anything the culture finds uncomfortable. The love of God has been sanitized, democratized, and above all sentimentalized. This process has been going on for some time…It has not always been so. In generations when almost everyone believed in the justice of God, people sometimes found it difficult to believe in the love of God. The preaching of the love of God came as wonderful good news. Nowadays if you tell people that God loves them, they are unlikely to be surprised. Of course God loves me; he’s like that, isn’t he? Besides, why shouldn’t he love me? I’m kind of cute, or at least as nice as the next person. I’m okay, you’re okay, and God loves you and me. Even in the mid-1980s, according to Andrew Greeley, three-quarters of his respondents in an important poll reported that they preferred to think of God as ‘friend’ than as ‘king’. I wonder what the percentage would have been if the option had been ‘friend’ or ‘judge’. Today most people seem to have little difficulty believing in the love of God; they have far more difficulty believing in the justice of God, the wrath of God, and the non-contradictory truthfulness of an omniscient God. But is the biblical teaching on the love of God maintaining its shape when the meaning of ‘God’ dissolves in mist? We must not think that Christians are immune from these influences.” (pp.11-12)

It is against this cultural and Christian backdrop that we must strive with a renewed fervor to learn what God’s love is; what it truly is. Because if we fail to understand the love of God, I am afraid that every other Christian doctrine will be negatively affected as a result. In a world full of many evils (such as war, illness, death and suffering) seemingly inconsistent with the general perceived notions of God’s love, it is more important than ever that we return to the Scriptures and allow God Himself to teach us about the different distinctions in the depiction of His love. So with that said, I will now summarise how D.A. Carson categorises the different ways God loves (please note, however, as Carson himself clarifies in his book, this list is not an exhaustive explanation but a mere scratching of the surface – so great and unfathomable is the love of God that you can spend your whole life trying to understand it).

But before I do that, let us first make some preliminary observations about God’s love. When the Apostle John tells us that “God is love” in his First Epistle (4:8), we should proceed with great caution and reverence in interpreting this most popular of Scriptural declarations. Before I get into what the word ‘love’ means here, I will first briefly note something about the other two words which are often overlooked in this verse; i) ‘God’ refers to His nature, most importantly His being a Triune God, a Holy Trinity of three persons in eternal communion; and ii) ‘is’ refers to His being eternal, immutable and transcendent, evoking a connection to God’s name “I AM” (Ex 3:14).

So how do these two comments help us interpret this verse? Well in order to understand how God is love, you must first understand that God’s love has eternally existed in His very being; the Trinity loves each other. As Ravi Zacharias observes, Christianity is the only religion where God’s love preceded creation; in every other religion God did not love until after creating distinct objects to love. But because Christianity affirms the Trinity, God prior to creation did not need to create any objects to love as He already constituted three distinct persons to love and to be loved. There eternally existed an “other-orientation” for God’s love within Himself (p.45). In particular, we are told in Scripture that the Father eternally loves the Son (Jn 3:35) and the Son eternally loves the Father (Jn 14:31).

Now when it comes to interpreting what the word ‘love’ means in 1 John 4:8, Carson heavily advises against falling into the trap of simply translating it from the Greek word used, ‘agapao’. Carson argues that whilst this Greek word is popularly translated as meaning willed altruism, this is not the definitive translation. It is often used interchangeably throughout the Bible with another Greek word for love, ‘phileo’, such as in John 3:35 and John 5:20. Carson demonstrates by these, and many other inconsistencies which I will not go into here, that the word ‘agapao’ used by John should be best translated as simply the way it is - ‘love’. And just as in English when interpreting the word ‘love’ with its varied connotations, Carson proposes that we let the context define and delimit the word.

Though God is sovereign, transcendent, immutable (Mal 3:6), omniscient (Mt 11:20-24), omnipotent (Jer 32:17) and impassible, these attributes do not contradict nor remove the affective element of God’s love. In fact, they, particularly His sovereignty and immutability, accentuate His love. It is not, as many think, that God was once full of wrath and hatred in the Old Testament, then changed and became loving in the New Testament. On the contrary, in both Testaments God is depicted as loving and wrathful; it is just that this love and wrath is made more clearly manifest by Christ in the New Covenant. Because God is unchangeable and eternal, it a great source of comfort to know that when He loves us, this love is concrete and nothing we can do can change this. This engenders stability and elicits worship; He is being and we are becoming; He is the great Rock (p.62).

But this unchangeability does not deprive God of emotions; it simply means He is not prone to passionate mood swings as we are. God loves with real emotive love; He rejoices (Isa 62:5); He grieves (Ps 78:40) and He gets angry (Ex 32:10). In 1 John 4:7-11, the same word is used for our love and God’s love. What this shows is that, whilst God’s love is obviously infinitely richer and purer than our own, God’s love is both the model and incentive for our love (p.55). We were made in God’s image, after all (Ge 1:27). We cannot divorce God from what He is in Himself and God as he interacts with the created order, these created image-bearers. Both our love and God’s love belong to the same genus or else a parallel could not be drawn; we would not be able to relate to Him nor vice versa. Thus, as we love with emotion (albeit, sin-tainted emotion), likewise, so God does. But as Carson cautions:

“All of God’s emotions, including his love in all its aspects, cannot be divorced from God’s knowledge, God’s power, God’s will. If God loves, it is because he chooses to love; if he suffers, it is because he chooses to suffer. God is impassible in the sense that he sustains no ‘passion’, no emotion, that makes him vulnerable from the outside, over which he has no control, or which he has not foreseen. Equally, however, all of God’s will or choice or plan is never divorced from his love – just as it is never divorced from his justice, his holiness, his omniscience, and all his other perfections…In that framework, God’s love is not so much a function of his will, as something that displays itself in perfect harmony with his will – and with his holiness, his purposes in redemption, his infinitely wise plans, and so forth.” (pp.68-69)

1) INTRA-TRINITARIAN LOVE

The first way God loves is what we discussed above in relation to His very nature; God is a Trinity of eternal love directed at one another. To merely touch upon what this love of God perpetually existing in the Trinity means, Carson plucks an example from a book of the Bible especially rich in these divine insights, John’s Gospel.

For this reason the Jews persecuted Jesus, and sought to kill Him, because He had done these things on the Sabbath. But Jesus answered them, “My Father has been working until now, and I have been working.” Therefore the Jews sought all the more to kill Him, because He not only broke the Sabbath, but also said that God was His Father, making Himself equal with God. Then Jesus answered and said to them, “Most assuredly, I say to you, the Son can do nothing of Himself, but what He sees the Father do; for whatever He does, the Son also does in like manner. For the Father loves the Son, and shows Him all things that He Himself does; and He will show Him greater works than these, that you may marvel. For as the Father raises the dead and gives life to them, even so the Son gives life to whom He will. For the Father judges no one, but has committed all judgment to the Son, that all should honour the Son just as they honour the Father. He who does not honour the Son does not honour the Father who sent Him…I can of Myself do nothing. As I hear, I judge; and My judgment is righteous, because I do not seek My own will but the will of the Father who sent Me.” (Jn 5:16-30)

What the Jews accuse Jesus of in this passage is ditheism. They misunderstand Jesus’ claims to be equal with God as asserting that He is an alternate and separate god to God. Jesus answers these false charges in verse 19a by explaining that He is not separate or an alternative to God, but on the contrary, He is totally dependent and subordinate to God the Father. But in the following part of verse 19 (b), Jesus then subtly reveals that this subordination is unique. Whilst relying completely on the Father, Jesus tells us that everything the Father does, likewise, so He does. As Carson says, ‘like father, like son’ (p.36).

In other words, though the Son is subordinate, this is only in function and the Son is equal to God the Father in deity and coextensive action (ie. to quote a famous adage, ‘if it looks like a duck, walks like a duck and quacks like a duck, then it’s probably a duck’; and Jesus not only ‘quacks’ like God only can, He ONLY ‘quacks’ like God only can). Jesus eternally existed as the Son both pre-Incarnation and post-Incarnation (p.42). Because Jesus ONLY does and says everything that the Father does and says, not just some things the Father does and some things on His own, the Son is a perfect revelation of the Father. As Jesus reveals in verses 20-21, Jesus is not merely an agent of resuscitation and God’s miraculous works as others such as Elijah were, but He is the actual doer of them Himself; He raises the dead like His Father can because the Father has shown Him how to do this from eternity. This includes creation (Jn 1:2-3). And why does the Father show the Son everything He does? Carson answers this thusly:

“Here the pre-industrial model of the agrarian village or the craftsman’s shop is presupposed, with a father carefully showing his son all that he does so that the family tradition is preserved. Stradivarius Senior shows Stradivarius Junior all there is to know about making violins – selecting the wood, the exact proportions, the cuts, the glue, how to add precisely the right amount of arsenic to the varnish, and so forth. Stradivarius Senior does this because he loves Stradivarius Junior. So also here: Jesus is so uniquely and unqualifiedly the Son of God that the Father shows him all he does, out of sheer love for him, and the Son, however dependent on his Father, does everything the Father does.” (p.39)

Likewise, in obeying everything the Father has commanded and by doing everything the Father does, this reveals the Son’s love for the Father (Jn 14:31). We must, of course, make a distinction between the love of the Father for the Son and vice versa. The Father demonstrates His love for the Son by commanding, sending, telling and commissioning, ‘showing’ Him everything (p.45). Conversely, the Son demonstrates His love for the Father by obeying, saying what the Father gives Him to say, doing what the Father gives Him to do, coming into the world as the ‘Sent One’, demonstrating His love for the Father by such obedience (p.45). The Son is equal with the Father in substance or essence, but is subordinate in an economic or functional respect.

This functional subordination of the Son to the Father establishes His perfect obedience and self-disclosure of God. And contrary to what us egotistical souls may think, Carson argues that this revelation revolves not around God’s love for us, but on the Father’s unique love for the Son (p.40). Whilst God saves us because He loves us (as we will later explore), the reason He primarily saves us is because He loves His Son and desires all peoples to honour and worship Him.

It is this Intra-Trinitarian love that the Father has for the Son that establishes the standard for all other loving relationships, either inter-human, or between the Divine and the world as John 3:16 shows. Yes, the Father loved the world. But we measure this love for the world by the act of Him giving the Son. The Father’s love for the Son is the measuring stick. Similarly, the Son’s love for the Father demonstrated by His obedience is the standard for remaining in the Father’s love (Jn 15:9-10) (we will also explore this in the last kind of love). We are ultimately called to mirror the intra-Trinitarian love of God in our various relationships.

2) GOD’S PROVIDENTIAL LOVE OVER ALL THAT HE HAS MADE (IE. COMMON GRACE)

“Therefore I say to you, do not worry about your life, what you will eat or what you will drink; nor about your body, what you will put on. Is not life more than food and the body more than clothing? Look at the birds of the air, for they neither sow nor reap nor gather into barns; yet your heavenly Father feeds them. Are you not of more value than they? Which of you by worrying can add one cubit to his stature? So why do you worry about clothing? Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow: they neither toil nor spin; and yet I say to you that even Solomon in all his glory was not arrayed like one of these. Now if God so clothes the grass of the field, which today is, and tomorrow is thrown into the oven, will He not much more clothe you, O you of little faith? Therefore do not worry, saying, ‘What shall we eat?’ or ‘What shall we drink?’ or ‘What shall we wear?’ For after all these things the Gentiles seek. For your heavenly Father knows that you need all these things.” (Mt 6:25-32)

What Jesus is here revealing and depicting is a God who lovingly provides food, drink, clothing and the necessities of life to all the fish of the sea, the birds of the air, and the creatures and plants of the land. Though Scripture does not explicitly call this providence ‘love’, there is a very clear sense in which God is the loving Creator who provides for His creation out of His generous love. Before sin entered the created world, God declared it ‘good’ (Ge 1-2). After sin entered the world, God could have destroyed it all. Not partially in the flood, but completely wipe it out. However, God in His Grace has decided to leave it and not only leave it, but provide good things for it.

This is what the Reformers called God’s Common Grace. In other words, it is made manifest and available to all without distinction. If God created you, He loves you in the very fact that He created you and gave you the gift of life in the first place. None of us have done anything to deserve being created, hence it is rightly called Grace. Furthermore, though you are a sinner, you still can benefit from this providential love of God; you can love, eat, drink, laugh, have a family and enjoy life. As Jesus says in Matthew 5:43-45, this undiscriminating providential love of God is the basis for the great command to love our enemies, “for [God Himself] makes His sun rise on the evil and on the good, and sends rain on the just and on the unjust.” As we will later see, this is one of the many ways in which the astounding love of God is used as the basis for our relationships with others.

However, this Common Grace is not guaranteed or eternal in its length, nor applied to all equally and similarly. Children die prematurely. Murders and wars happen every day. There are some in the world who die from famine and poverty. This is still a fallen world and the results of sin are clearly evident. But as Jesus assures us, “not one [sparrow] falls to the ground apart from your Father’s will” (Mt 10:29) and thus, God is in control of life and death. He is sovereign. The Lord gives, and the Lord takes away (Job 1:21).

Yet, this love of God shown through Common Grace does not overrule God’s wrath upon sinners, but actually coexists with God’s wrath. That old cliché of Ghandi’s which has been dangerously appropriated into Christian theology, culture and language; that God “hates the sin but loves the sinner”; is actually mostly false when talking about God’s love and His wrath, Carson argues (p.79). Throughout Old and New Testaments, God declares His hatred not only for sin but also for the sinner themselves; God’s wrath is both on the sin (Ro 1:18) and on the sinner (Jn 3:36). Though God’s hatred depends on the object of His wrath, because God’s love does not depend on the object’s loveliness, God can be both loving and wrathful to the same individual. Though God loves all of us through Common Grace, He also is wrathful towards us because of our sinfulness. The only love of God which overrules and satisfies this wrath is the fourth love which we will discuss later.

3) GOD’S SALVIFIC STANCE TOWARD HIS FALLEN WORLD

“For God so loved the world that He gave His only begotten Son, that whoever believes in Him should not perish but have everlasting life.” (Jn 3:16)

Though many (including, admittedly, myself) may try and twist this most famous of verses from Scripture to refer only to the salvific love God has for His elect, it is clear from a study of Johannine theology that the word ‘world’ (or ‘kosmos’ in Greek) refers primarily to “the moral order in willful and culpable rebellion against God” (p.18). In other words, this verse, rather than emphasising the bigness of the world that God loves, emphasises the badness of the world that God loves. As Carson says, “In John 3:16 God’s love in sending the Lord Jesus is to be admired not because it is extended to so big a thing as the world, but to so bad a thing; not to so many people, as to such wicked people” (pp.18-19).

Though the elect are chosen, saved and drawn out from the world (Jn 15:19), God loves both the elect and the world, albeit in different ways. This love God has for the world is made most manifest by the Great Commission in Mark 16:15; that the Gospel is to be preached to every creature in the world. God loves the world in this sense by inviting and commanding all humans everywhere to repent and believe the Gospel, calling out, “As I live…I have no pleasure in the death of the wicked, but that the wicked turn from his way and live. Turn, turn from your evil ways!” (Eze 33:11).

It is important to note here, however, that though God is said to love the world, we are also told not to love the world (1Jn 2:15-17). This seeming contradiction whereby God is commended for His love for the world and yet, we are prohibited from loving this same world can be explained away by the distinction between God’s love and our love in this context. As Carson summarises this point, “God’s love for the world is commendable because it manifests itself in awesome self-sacrifice; our love for the world is repulsive when it lusts for evil participation. God’s love for the world is praiseworthy because it brings the transforming gospel to it; our love for the world is ugly because we seek to be conformed to the world. God’s love for the world issues in certain individuals being called out from the world and into the fellowship of Christ’s followers; our love for the world is sickening where we wish to be absorbed into the world” (p.91). That said, though the way we love the world in this way is prohibited, we are still encouraged to imitate the way God loves the world by preaching the Gospel to everyone in it.

Instead of destroying the world once and for all as He would be just to do, God sent His Son into this dark world, though it deserved not this most precious of gifts (Jn 1:10-11), so that it may be saved. But as though sending His Son to die for the sins of the world were not enough, God goes one step further in the next way He loves.

4) GOD’S PARTICULAR, EFFECTIVE, SELECTING LOVE TOWARDS HIS ELECT (IE. SAVING GRACE)

God in His love has sent His Son into this rebellious world to die so that it may be saved through believing the Gospel. However, there is only one problem with this – man in his natural Total Depravity cannot and will not believe the Gospel (Jn 6:65). At this point, after not only creating and providing for us (the second love) and sending His Son to save us (the third love), God could have now thrown up His hands and exclaimed, “These foolish and sinful men; not only do they refuse to give Me praise for the gifts of life I lovingly provide for them, but they now reject My Son and My offer of Salvation! I give up – I shall now just destroy them all!” I know that’s probably what I would do.

But in His immeasurable love, God goes one step further and chooses some undeserving sinners out of the world whom He changes through His Spirit by His Grace so that whereas before they had hardened hearts and wills which rejected His offer of Salvation, afterwards they have hearts and wills which respond positively to the Gospel and can hence believe. This is what the Reformers called Saving Grace (please note, I will not get into a discussion now about the arguments for the Calvinist doctrines of Unconditional Election and free will, but if you are interested, read my earlier blog titled “Un-Free Willy [Part 1]”). We see this exemplified in the Old Testament with the way the Scriptures describe how God loved Israel.

“For you are a holy people to the Lord your God; the Lord your God has chosen you to be a people for Himself, a special treasure above all the peoples on the face of the earth. The Lord did not set His love on you nor choose you because you were more in number than any other people, for you were the least of all peoples; but because the Lord loves you, and because He would keep the oath which He swore to your fathers, the Lord has brought you out with a mighty hand, and redeemed you from the house of bondage, from the hand of Pharaoh king of Egypt.” (Dt 7:6-8)

This, and many other passages in Scripture, shows the contrast between God’s people and the other nations of the world. What’s interesting to note is that the distinguishing feature between Israel and the other nations has nothing to do with any merit or inherent quality on their part, but rather has everything to do with God’s love and good pleasure. God chooses to save and redeem His people because He loves them in a way unique to other nations of the world. As God says in Malachi 1:2-3, “Jacob I have loved; but Esau I have hated.” The Apostle Paul later comments on this verse in Romans 9:11-13, explaining that this saving and electing love for Jacob is directed towards him not because of anything he has done better than Esau, as God declares this love toward Jacob before he or his brother were born, but because of God’s purposes.

Husbands, love your wives, just as Christ also loved the church and gave Himself for her, that He might sanctify and cleanse her with the washing of water by the word, that He might present her to Himself a glorious church, not having spot or wrinkle or any such thing, but that she should be holy and without blemish. (Eph 5:25)

This sort of language is now used in the New Testament for Christ and His Church. God’s electing love now extends to Spiritual Israel; individuals from all nations on Earth make up the Church. We as the Church have been saved and now exclusively and uniquely experience the love of Christ manifest as our friend (Jn 15:14-15). Jesus makes the distinction here between a slave and a friend. But this difference lies not in a duty to obey and submit, or even of ownership as we are still commanded to obey Christ and submit to Him as He has bought us with His blood. Far from a notion of friendship as cheap human intimacy which we are often guilty of doing by calling Jesus our ‘best friend’ and bringing Him down to our level, this friendship is based on the Son’s disclosure to us of divine revelation. We are still His inferiors, yet “we have been incalculably privileged not only to be saved by God’s love, but to be shown it, to be informed about it, to be let in on the mind of God. God is love; and we are the friends of God” (p.49).

This saving, electing love of God is best exemplified in the Reformed doctrine of Limited Atonement. Carson prefers the term definite atonement and argues thusly (p.84). In other words, when God sent His Son to the Cross, He thought of its effect for His elect differently to its effect for others in the world. Carson argues that the Cross is definite in its atonement based more on God’s intent in Christ’s work than on the extent of its significance (p.85). Christ died to save His people (Mt 1:21); and as we saw above in Ephesians 5:25, Christ died specifically for His Church, so that He could purify a peoples exclusively for Himself (Tit 2:14). As Carson puts it, “In his death Christ did not merely make adequate provision for the elect, but he actually achieved the desired result (Rom. 5:6-10; Eph. 2:15-16)” (pp.85-86).

And to the Arminian who asserts that Christ died for the sins of the whole world, Carson replies that the Apostle John does not assert here that the atonement is effective without exception (as though those unread in Johannine theology would ignorantly assert he were a universalist), but rather that the atonement opens up a potential for all without distinction (p.88). As the old Calvinist adage goes, Christ’s sacrifice is “sufficient for all” (ie. the third kind of love), but only “effective for some” (this saving, electing love of God presently discussed).

And what’s more, nothing we can do can stop God loving us in this way. Once God has set this saving love upon you, He will not lose you (Jn 6:37-40). Carson explains this point brilliantly and humorously using an analogy of a young in-love couple:

“God does not ‘fall in love’ with the elect; he does not ‘fall in love’ with us; he sets his affection on us. He does not predestine us out of some stern whimsy; rather in love he predestines us to be adopted as his sons (Eph. 1:4-5)…We may gain clarity by an example. Picture Charles and Susan walking down a beach hand in hand…Charles turns to Susan, gazes deeply into her large, hazel eyes, and says, ‘Susan, I love you. I really do.’ What does he mean?…If we assume he has even a modicum of decency, let alone Christian virtue, the least he means is something like this: ‘Susan, you mean everything to me. I can’t live without you. Your smile knocks me out from fifty metres. Your sparkling good humour, your beautiful eyes, the scent of your hair – everything about you transfixes me. I love you!’ What he most certainly does not mean is something like this: ‘Susan, quite frankly you have such a bad case of halitosis it would embarrass a herd of unwashed, garlic-eating elephants. Your nose is so bulbous you belong in the cartoons. Your hair is so greasy it could lubricate an eighteen-wheeler. Your knees are so disjointed you make a camel look elegant. Your personality makes Attila the Hun and Genghis Khan look like wimps. But I love you!’ So now God comes to us and says, ‘I love you.’ What does he mean? Does he mean something like this? ‘You mean everything to me. I can’t live without you. Your personality, your witty conversation, your beauty, your smile – everything about you transfixes me. Heaven would be boring without you. I love you!’ That, after all, is pretty close to what some therapeutic approaches to the love of God spell out. We must be pretty wonderful because God loves us. And dear old God is pretty vulnerable, finding himself in a dreadful state unless we say yes…When he says he loves us, does not God rather mean something like the following? ‘Morally speaking, you are the people of the halitosis, the bulbous nose, the greasy hair, the disjointed knees, the abominable personality. Your sins have made you disgustingly ugly. But I love you anyway, not because you are attractive, but because it is in my nature to love.’ And in the case of the elect, God adds, ‘I have set my affection on you from before the foundation of the universe, not because you are wiser or better or stronger than others but because in grace I chose to love you. You are mine, and you will be transformed. Nothing in all creation can separate you from my love mediated through Jesus Christ’ (Rom. 8). Isn’t that a little closer to the love of God depicted in Scripture?…At the end of the day, God loves, whomever the object, because God is love…his love emanates from his own character; it is not dependent on the loveliness of the loved, external to himself.” (pp.69-72)

In God demonstrating that He loves the unlovable, this should spur us on to likewise love our unlovable enemies; once again showing that God’s love is the model and standard for our own relationships. This love is far deeper, richer and greater than any love God has for any of His creation. Everyone on earth, as the Creator’s creation, enjoys the love the Creator has for them. Only God’s elect and chosen people enjoy the privilege of being called God’s children (Jn 1:12-13), experiencing the love of God who manifests Himself to them as their Father. And this privilege comes through God’s choice and will by Grace, not through human choice or will, lest there be room for boasting and it cease to be called Grace; the distinction between the believer and the non-believer lies not in themselves, but in God’s electing and gracious love. After all, “we love Him because He first loved us” (1Jn 4:19).

This electing love, ironically, should also spur us on to preach the Gospel of the love of God to EVERYONE without exception, both in His salvific stance and His electing love. However, it is very important that, in preaching that God loves every sinner, we do not mix the two and hence ignore, cheapen or diminish the unique love that God has for His people. It has become so widely believed that God loves the world that this has become confused with His love for the Church; Common Grace and Saving Grace have been so marred and blurred together that they have become indistinguishable. Scripture makes a clear distinction between the two ways God loves.

And as Carson astutely points out, God does not, as opposed to popular opinion, ‘love everyone the same.’ His love, Carson argues, is far more complex than our “mere sloganeering” (p.27). John MacArthur corrected this common misperception regarding Common Grace and Saving Grace in one of his sermons, "http://www.gty.org/Resources/Sermons/80-192">Man Rejects, But God Loves:

“All people are rejecters of God’s love by nature, and they frankly can do nothing about it. They have not the capacity to please God. They have not the disposition to love God. But God, in sovereign love, and unique love, penetrates through that universal rejection to forgive and save some sinners, in spite of their rejection. Not because they reject less than others. Not because they deserve salvation more than others. But purely on the basis of his own will, and his own desire, and his own sovereign love, he determines to penetrate that universal rejection, and rescue those upon whom he decides to set his saving love. This is another kind of love. This is a different kind of love. Different in degree, and different in extent. That first love we talked about [Common Grace] is greater in extent, lesser in degree. That saving love is greater in degree, and lesser in extent. God does love the world. The Bible makes that clear. He loves the world with a generous, sparing, grieving, compassionate, providential, warning, love that even offers the gospel. But sinners reject it…[and] God’s love spurned gives way to divine hate, manifested in eternal judgment. And while this love is universal in its extent, and it is limited in degree, it is not the sort of love that saves everybody…There is a love that does save. The love that does save is less in its extent, that is, it’s applied to fewer. It’s greater in degree, because it saves them forever.”

5) GOD’S CONDITIONAL OR PROVISIONAL LOVE DIRECTED TO HIS OWN PEOPLE

This final way God loves follows on from the previous category of God’s love; it is directed toward those whom He has chosen to save. Part of being saved is coming to know God both intellectually and intimately. An element of this relationship is that God’s love is conditional on our obedience. This is not to say if we don’t obey Him we won’t be provided for (as we have above seen, God’s providential love is hard to escape), nor does it mean that we will lose our Salvation (again, as we have already seen, God’s election is unconditional), but this kind of way God loves is conditional.

As Jude commands us in his letter, “Keep yourselves in the love of God” (v.21). By this simple command, Jude is implying that there are Christians who may not at certain times keep themselves in God’s love. Likewise, Jesus gives a similar command in John 15:10 when He says, “If you keep My commandments, you will abide in My love.” This theme of God’s relational love being conditioned upon His covenant people’s obedience to His commands is found throughout Scripture such as in Exodus 20:6 and Ps 103. If you are still trying to struggle to understand this love of God, I will recount an analogy that Carson uses:

“To draw a feeble analogy: although there is a sense in which my love for my children is immutable, so help me God, regardless of what they do, there is another sense in which they know well enough that they must remain in my love. If for no good reason my teenagers do not get home by the time I have prescribed, the least they will experience is a loud telling off, and they may come under some restrictive sanctions. There is no use reminding them that I am doing this because I love them. That is true, but the manifestation of my love for them when I ground them and when I take them out for a meal or attend one of their concerts or take my son fishing or my daughter on an excursion of some sort is rather different in the two cases. Only the latter will feel much more like remaining in my love than falling under my wrath.” (pp.21-22)

In other words, what this analogy conveys is that this kind of way God loves us is as a parent to a child (Heb 12:4-11). Whilst we may disobey our Father, the result of this will be the temporary experience of His disciplinary wrath. But this passing punishment does not mean God does not love us anymore or will take our Salvation away; heck, even the punishment itself is inflicted out of love.

Waves

Well, that went way longer than I expected (although I’m sure by now you have come to expect length from me; one of these days I shall shock you all by posting a blog of only one paragraph). Anyway, I hope these different categories of God’s love have made you aware of the richness and complexity of something we not only take for granted, but undervalue and oversimplify. That said, as Carson cautions, it would be very dangerous and harmful to our views of God if we were to absolutise any of these categories:

“If the love of God is exclusively portrayed as an inviting, yearning, sinner-seeking, rather lovesick passion…it steals God’s sovereignty from him and our security from us…If the love of God refers exclusively to his love for the elect, it is easy to drift toward a simple and absolute bifurcation: God loves the elect and hates the reprobate. Rightly positioned, there is truth in this assertion; stripped of complementary biblical truths, that same assertion has engendered hyper-Calvinism…If the love of God is construed entirely within the kind of discourse that ties God’s love to our obedience…, the dangers threatening us change once again…divorced from complementary biblical utterances about the love of God, such texts may drive us backwards toward merit theology, endless fretting about whether or not we have been good enough today to enjoy the love of God…In short, we need all of what Scripture says on this subject, or the doctrinal and pastoral ramifications will prove disastrous.” (pp.24-25)

We must also be careful we don’t compartmentalise them and think of them as separate and independent to one another; on the contrary, they overlap and are interlinked. I pray with Carson that we “learn to integrate them in Biblical proportion and balance” (p.26), not allowing one ‘love’ to diminish others.

Nevertheless, I also pray with Carson that you do not merely understand God’s love, but go beyond sheer analysis and receive, absorb and feel the very love of God in your own lives (Eph 3:17-19) (p.92). As he wisely says, “never, never underestimate the power of the love of God to break down and transform the most amazingly hard individuals” (p.93). Such is the Glorious God of love that we have! So until next time, put that in your cloud and rain it (Jude 12).

Christus Regnat,

MAXi